Food for Thought: The First Course

18th February 2021

By Tania Alliod, Rural Development Officer for the Cairngorms National Park Authority

Right now, a circular economic approach is what will help businesses and communities make a step change towards reducing CO2 emissions, reaching Scotland’s Net Zero goal by 2045, and bring benefits to our health and well-being. This was central to the discussions at the Highland Good Food Conference, where a vision emerged based on three pillars: our land, our people and diversity.

What is a circular economy?

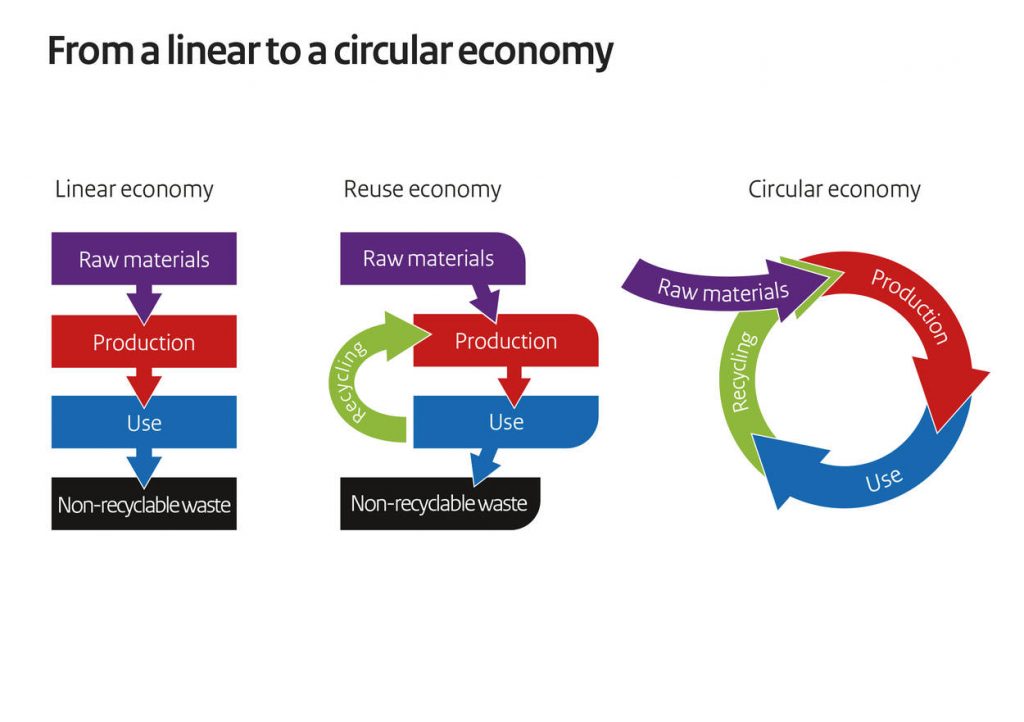

Definition: A circular economy (often referred to simply as “circularity”) is an economic system aimed at eliminating waste and the continual use of resources.

The historic system sees natural resources and materials go in one end and products, grown or manufactured, come out the other end to be processed and distributed to retailers, wholesalers and finally consumers. When these products come to the end of their useful life they are discarded as waste.

A circular system aims to be regenerative. From the start waste is designed out of the system; reuse it, re-purpose it, recycle it. Circularity sees that scarce natural resources are used efficiently at every stage from production and processing through to distribution, retail, consumption and finally waste management.

The Highland Good Food Conference

In January and February 80 delegates, from across the Highlands, came together virtually to consider what an ideal Highland Good Food Economy would look like. The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) sponsored four delegates in the Park who embed local food in their business to attend, including a landowner and producer, brewer, chef, and a tourism business.

Delegates shared experiences spanning the whole food sector, from chefs and crofters, to community growers, brewers, restauranteurs, landowners, food retailers, processors, retailers and third sector distributors. Each week five short thought–provoking presentations were delivered by guest experts on topics such as glasshouse production, soil science, seed and land management to micro-community distribution networks.

Delegates were invited to be bold and visionary, exciting ideas along with useful case studies were shared as we considered each stage of a future Highland circular food economy.

Our Natural Food Assets

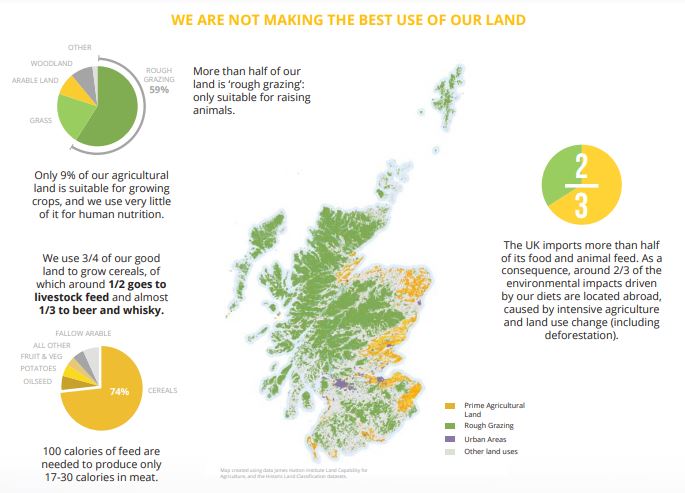

Bearing in mind our climate for growing crops and soil quality, Nourish Scotland still suggests we could be making better use of our natural land asset. Currently, 9% of agricultural land is suitable for crops and 75% of what we do grow goes to livestock feed and whisky production – not directly for human consumption.

Bringing more land into food production, at different scales, for human consumption is possible in the Highlands. Community growing projects and allotments are thriving, with more communities looking for land to bring into production. Currently, in the Park there are active projects in Kingussie, Dulnain Bridge and Braemar.

Lynbreck Croft, run by Lynn Cassells and Sandra Baer, is an inspiring story of what can be achieved in crofting. In just five years, they have transformed Lynbreck into an agri-tourism croft that serves the community and visitors, not just with produce but with guided visits and courses where they share their knowledge and learning.

Currently, there is more demand for crofts than available supply and making use of marginal land will be critical in our need to adapt to climate change. Visiting the Crofting Commission and the Scottish Land Matching websites is the first step for those seeking crofting opportunities.

It is not suggested that there should be an immediate paradigm shift in land use from crops for whisky and livestock feed, or that community growing should replace the convenience of supermarkets. But there is an opportunity to bring more land into production for seasonal fresh produce, grown locally and stimulate local demand too.

Playing to Our Strengths and Adapting to Our Environment

In the Cairngorms National Park we are producers of excellent protein; venison, beef and lamb are all raised and sold locally. Rothiemurches Estate raises and butchers its own venison, sold through their retail food shop and Balliefurth Farm sells directly to customers at their farm shop in Nethy Bridge.

An often-heard argument against buying local Park-reared meat is that it is more expensive than the supermarket alternative. But supermarket prices do not factor in carbon costs – if included, our weekly shopping bills would skyrocket. Locally produced and sold meat is priced according to real production costs and importantly has virtually no external carbon emission costs (road miles, processing energy and waste). It also comes with the added benefit of knowing where your food comes from, knowing it is reared in a healthy environment and is not mass-produced in poor environmental and health conditions.

Then there is our fickle climate and poor Highland soils, that do not lend themselves to reliable and regular crops of fruit and veg. Mike Rivington from the Hutton Institute explains how we tackle this in his excellent presentation; What needs to happen to make producing local food sustainable?

While soil science and technology can help improve quality, that still leaves the climate. One big and exciting idea raised by Pete Ritchie of Nourish Scotland certainly stimulated everyone’s imaginations at the Conference. His proposition was that our Highland fresh fruit and veg needs could be met by bringing production undercover, in glasshouses or poly–tunnels, but on an ambitious scale, making the Highlands “the Mediterranean of the North”. With improved soil quality and utilising wind energy and ground source heat (poly–tunnels/glasshouses would be partially submerged to capture this heat) the Highlands could become self-sufficient in fruit and veg, and even produce excess for sale.

Ritchie estimates that in order to feed the 250,000 people living in the Highlands their 400g of fruit and veg a day, would require 9,000 tonnes of fruit and veg. His model estimates this could be produced by 18 hectares of glasshouse/polytunnel for an initial investment of £1million/ hectare. For an investment of £18 million the Highlands could become self-sufficient in fruit and vegetables, an idea to tick all boxes; Net Zero and the circular economy – grow it, sell it, eat it, all in the Highlands.

Added to this, glass farming creates sustainable, year-round green jobs and encourages the development of new and diverse skills. Such a vision has the potential to all but eliminate our current fruit and veg carbon miles and create a near-perfect circular economy. It is already being done, in Finland, with a population of 5.5 million, they currently have 394ha of glasshouses producing fruit, vegetables, and flowers. In the Park we already have some expertise to tap into, 10 years ago at Drumuillie, near Boat of Garten, asparagus was being grown successfully in 3 large poly–tunnels and sold locally. Just outside the Park the Tarland community garden is thriving.

Such a production shift couldn’t happen before a review of current agriculture subsidy policies. And end incentives will need to be available for larger-scale food producers and regenerative food production at smaller scales.

Look out next week for the second course of Tania’s Food For Thought blog where she explores the challenges of processing and distribution in the Highlands.