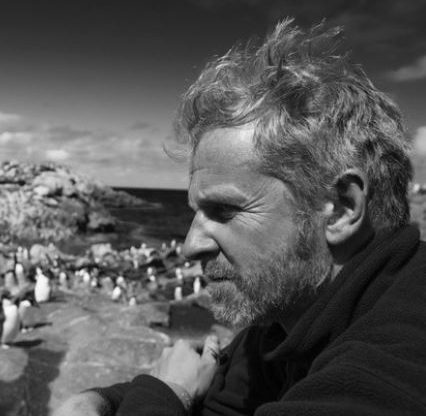

Guest blog from Mark Flowers – BBC Springwatch Producer

9th May 2019

Mark Flowers is the Series Producer for the BBC’s hugely popular ‘Watches’, which are based here in the Cairngorms for 2019. We asked him to tell us about his first impressions of the Cairngorms National Park and why it is such a special place for nature.

Ever since I can remember I have been fascinated and perhaps even what we might say entranced with Nature, and particularly the wildlife of Britain’s mountains and uplands. Back in the mid sixties my parents decided to leave Birmingham and rear a family in the Yorkshire Dales, a decision for which I will always be thankful. Now, as I get older, it’s legacy has more and more impact on me. I marvel at it because not only did it give me a life long passion, it also gave me a way of life, and ultimately it brought me to the Cairngorms.

It also led to me uttering a phrase, which, as a proud Yorkshireman, is almost unimaginable. When asked by a Scottish Colleague how I felt about my first visit to the Cairngorms, I uttered these sacrilegious words: “The Cairngorms – like Yorkshire only better” , and then once the words had escaped my mouth I looked at her ( the script supervisor……. in the broadcast truck gallery five minutes before our first live broadcast of Winterwatch) in a state of wide eyed shock and exclaimed “what have I just said?” The result was peals of delighted laughter, and try as I might I just couldn’t retract it. The Cairngorms really are the most magnificent scenery I’ve seen on our shores, and the more I analysed it in my mind, the more I realised it was true!

I grew up in the natural world of Wuthering Heights, a place of tumultuous skies, infinite landscapes, enchanted woods and dramatic seasonal change, which defined the rhythm of our lives. A place and a way of life which would sow a seed that came to life forty years later, last November, when I first visited the Cairngorms. However, before I reveal how I felt about that, I’d better tell you the reason my first visit to this part of Scotland was, personally, so special for me.

Back in Yorkshire, when we were tiny, on warm Sundays when the weather and mood was right, we’d pack up the old Renault 16. Grandparents would come to along with Jess the dog ( a supremely clever black lab), and we’d go for picnics in what I call “the Majesty”, the Upper Dales where the winds blow, the Curlews cry and the wild fells stretch ahead as far as you can see. Your spirits lift with the skylarks and time seems to stop. The experience was all washed down with Wensleydale cheese ( of course!) and chutney sandwiches and Heinz tomato soup from the thermos. These trips to the “highlands” gave me a curious and abiding love of Upland Britain and its iconic and distinct plants and animals, from cotton grass to gentians and from Peewits to Mountain Ouzels.

At home we had a wonderful Bird book with beautiful images, the readers digest book of British Birds – it has a Barn Owl on the front, and each page has a beautiful illustration and opposite lots of delicious facts and figures, ideal fact and art fodder for young amateur naturalists and future visitors to Scotland.

After our adventures in the hill tops , we’d race back to look up the birds we’d just seen, not only did we pore over where Curlews migrated too, where Ravens might live, we also discovered the pages of Scottish species which seemed too good to be true: the Osprey -a fishing eagle that came from Africa, the wildly impossible, unfeasible Capercaillie and legend of legends the Golden Eagle with that ferocious glint in its eye and talons that you couldn’t comprehend . How our imaginations soared as we contemplated these illustrations as living creatures.

However one of the consequences of growing up in upland Britain, is mountain weather, and after a few rain ruined holidays in the Lake District and an incident when we were imprisoned in a caravan by freezing cold winds, my parents took us south to the sun for our holidays and I never really ventured any further North. Now all that has changed.

Fast forward thirty years to November last year and you’d see me with my colleague Chris driving North out of Edinburgh Airport. As soon as you head over the Forth Bridge you know you are in Scotland, there are mountains on the horizon, there are mountains just beyond the curve of the road, and the land seems well, huge. You know you have arrived in a different, wilder land and you can see why millions of people flock to Scotland each year . The A 9 snakes away from Edinburgh heading ever North into ever increasingly majestic scenery, this was the road I took in November for my fist ever visit to the Cairngorms.

When we arrived at the RSPB’s Forest Lodge at Nethy Bridge, I recall tumbling out of our hire car, and being bundled, immediately, into a Land Rover and then being driven off into the wild by the incredibly welcoming Jess Tomes from the RSPB. Immediately I thought I was in a land of legend, a character in Norse Fairy Story. The view outside the landy was off the richter scale for me…

Along with the awesome birds in the old family bird book, the other Cairngorms character that I’d always dreamed of encountering was the Caledonian Pine. I seriously love ancient trees, both as species and as characters. An old tree is an island in time, it has it’s own story to whisper to you, a song picked up over centuries. For me Caledonian Pines are the Ice age writ large. I’d seen them on tv ( in earlier series of Springwatch!), I’d read about them in books, I’d seen them planted in English parks and Gardens, but nothing prepared me for a swathe of old growth Caledonian Forest in the Flesh It is overwhelming and so, so different to anything I’ve ever seen in England and on my own home patch of Yorkshire.

What stuck me was the scent, the texture, the “design” – the way the trees look like giant Bonsais as if trained and sculpted by a fantastic garden designer. When young Caledonian Pines look like bushy Christmas trees but as old “granny Pines”, the Trees feel as if they have been beamed in from ten thousand years ago. You can imagine them watching Mammoths and giant Irish Elk.

Where I grew up heather and bilberries grow on moors and open hilltops. Here in the Cairngorm forest they embrace the forest floor as a living, leafy blanket under the shade of the evergreen trees, I looked through the tree trunks and thought I was in the wild woods of Canada or Scandanavia. I’m sure I felt the ghosts of wolves. What struck me was that each tree seemed to have a halo of silver-gold lichen. Even though it was November, it was a cold grey day and the woods were like a painting full of textures and hues that moved from greys, to blondes to hazy purple – utter natural magic. This was the realm of the magnificent beast and birds I’d seen on TV or in our family’s old book.

And then, as we drove higher and higher the woods thinned and we stopped. I raced round the front of the car and the view literally blew me away. I was in another world, no sign of human habitation anywhere, and there on a high hill I got my first staggering view of the Cairngorms…

The endless vista of wilderness stretched out ahead: a perfectly composed view of a loch, a flat valley floor with fingers of ancient Caledonian forest, swathes of rolling moors and beyond that the rounded spectacular massif of the Cairngorm mountains. The place where the eagles cry, the deer roam, the wildcat stalk and pine martens scamper. Wow, I thought, this was a dream come true, a visit that had taken me forty years to make and as I looked out at the land – the back of my mind whispered the phrase – “Like Yorkshire only better”.

If you want to be inspired as Mark was then why not Discover and explore the Cairngorms National Park for yourself.

Having started his career as researcher on David Attenborough’s Private Life plants in 1991, Mark Flowers has developed a reputation as a creative storyteller and programme-maker who has worked on series including “Earth’s Great Rivers”, “New Zealand – Earth’s Mythical islands” and the “The Natural World”. He is currently the Series Producer of the BBC’s Winter, Autumn and Springwatch programmes.